Please be patient, this web page takes a moment to load.

Protein

Propaganda:

Deciphering Fact from

Fiction

Today's

supplement market abounds with propaganda and misinformation purposely

generated to confuse consumers so that companies marketing proteins and

other nutritional items can drastically increase their overall profitability.

Technical jargon is commonly used to cloud consumer perception of what

a product should cost and to make commonplace ingredients seem larger

than life. Why? Quite simply, because unscrupulous companies (most of

which don't even manufacture their own products) know the more spectacular

they can make a product sound, the more they can sell - which equates

to more money in their pockets. So called, "advanced delivery systems",

ridiculous claims of Biological Values (BV) well in excess of 100, misleading

"before-and-after" pictures, and far reaching references to the scientific

literature are just a few examples of the tactics that companies are currently

using to sell protein supplements. Judging from the fact that some

companies continue to propagate them, it's apparent that they have realized

huge profits from these devices; but at what cost? These shady marketing

campaigns have tarnished consumer perspective about protein supplements,

and more specifically - the type of protein(s) being used to produce these

supplements.

Not

Anti-Protein... Just Anti-Hype!

There's no doubt

about it, consuming adequate amounts of high-quality protein is essential

for continual gains in strength, tone and size. This is especially true

for athletes since active people certainly require more protein than

sedentary individuals (i.e. your average couch potato). But some companies

would have you believe that their products can do anything. Don't be

fooled by the hype! Let's face it; protein serves many functions in

the body but a protein supplement isn't going to turn you into the next Mr.

or Ms. Olympia, especially if you don't eat right, train hard, reduce

stress and get enough rest each night.

Protein,

in a Nutshell

Athletes,

particularly strength-training athletes, love protein. Many are fixated

on how much protein they consume, what sources they use, which foods

/ supplements they combine protein with, even what time of day they

take it. No surprises here. But what may surprise you is the number

of athletes who buy, use and reorder these items without even understanding

what they do or why they use them. In fact, we answer more questions

(e.g. What is it? What it is used for? Why do I need protein?) about

protein than just about any of the over 400 other products that we manufacture.

This cursory overview is intended to address many of these topics and

was included to provide a basic understanding about the importance of

proteins and amino acids.

Proteins are distinct

from other macronutrients (carbohydrates, fats and alcohol) in that

they are comprised of chains of nitrogen-containing subunits called

amino acids. All amino acids are important due to the fact that they

are the primary source of dietary nitrogen (an essential element). However,

some can be synthesized in the body from other materials and for this

reason are not considered essential. Of the 22 amino acids commonly

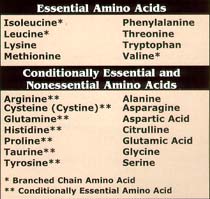

found in nature, eight (please refer to TABLE 1) are essential because

the body is unable to manufacture them at any point throughout the lifecycle.

These amino acids, aptly named essential amino acids (EAAs) must be

obtained in appreciable amounts and on a consistent basis from exogenous

sources (foods or dietary supplements) to prevent deficiency. Seven

other amino acids are considered conditionally essential (CEAAs) because

the body may have difficulty synthesizing them, or enough of them, under

certain conditions such as illness, surgery, extreme emotional stress

and intense physical activity. The remaining amino acids can be produced

as needed, provided the body has access to all the necessary raw materials

(nitrogen, carbon, sulfur, etc.), and are therefore classified as nonessential

amino acids (NAAs). Using the three groups of amino acids mentioned

above, the body polymerizes (links) elaborate chain-like molecules called

proteins. Among other things, proteins function: (1) to maintain body

structure (e.g. collagen, keratin, elastin); (2) in transport (e.g.

hemoglobin, albumin); (3) to facilitate movement (e.g. actin, myosin);

(4) in metabolism (e.g. numerous enzymes); (5) in immune function (e.g.

immunoglobulins); (6) in regulation (e.g. various hormones, neurotransmitters).

More importantly, at least to many page 3 bodybuilders and athletes,

amino acids are the "building-blocks" of lean muscle tissue.

Table1

The body's ability

to synthesize these and thousands of other proteins is dependant upon

the availability of all the amino acids at any given time. Unlike carbohydrate

and fat, which are stored as glycogen and triglycerides, respectively,

the body only maintains a very small pool of amino acids. If one or

more of the EAAs in this pool is low, the body is unable to complete

synthesis of any of the proteins calling for this/these amino acids.

Scientists often compare amino acids to letters in the alphabet and

intact proteins to words to help people better understand the importance

of having all the amino acids present when protein synthesis takes place.

Using this analogy, one could easily imagine how difficult it would be to construct

words and sentences without letters. Disturbingly, even short-term EAA

or CEAA deficiencies can stifle the important repair and rebuilding

process associated with all healthy cells, especially growing muscle

cells. Luckily, this scenario can be easily prevented with a well balanced

diet containing adequate amounts of high-quality protein. Current research

indicates that one half to one gram of quality protein per pound of

body weight (0.5 - 1.0 g protein / lb of body weight) is sufficient

for most any athlete. This is especially true if your overall caloric

intake is great enough to prevent the utilization of amino acids for

fuel.

Protein

from Foods vs. Supplements

It is possible

to get all the nutrients you need from foods, if you plan and prepare

your meals carefully. At minimum, daily meal planning involves a considerable

amount of time, shopping savvy and recipes. To complicate matters, it

can be very difficult to find foods/recipes that contain every thing

you want without all of the things you'd rather not have. For instance,

foods that are rich in protein (e.g. beef, whole eggs, pork) also tend

to contain appreciable amounts of fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and

unwanted calories. What's more, these foods often require refrigeration

and careful handling to minimize exposure to potentially harmful microbes.

Last, but not least, these foodstuffs commonly require cooking, which,

in turn, necessitates time, cleaning, kitchen space and utensils and

some rudimentary cooking skills.

In contrast, protein

and meal replacement supplements generally require little more than

a glass, some water or your favorite beverage and a spoon to prepare.

These dietary aids require no refrigeration until they are mixed and

they are portable enough to be carried in a gym bag or purse. Furthermore,

protein supplements are often more cost effective than many protein

rich foods and allow for better calorie / macronutrient control. Protein

/ Meal Replacement supplements are also a means through which individuals

with limited appetites can increase their daily protein / caloric intake

without consuming inordinate volumes of food. Regardless of which combination

you end up using, a good quality protein will provide high levels of

the amino acid categories (see Protein in a Nutshell), especially EAAs.

Eggs, dairy products, meats, fish and poultry are among the best food

sources, while whey, egg albumen, casein and soy protein are great supplement

choices.

Considering

A Supplement?

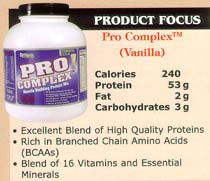

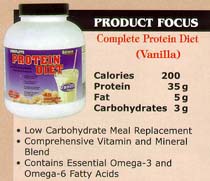

To say that

there are several protein supplements commercially available to athletes

would be a gross understatement. The average health food store or gym

carries scores of products, many of which are protein based. There are

whey proteins, milk proteins (casein rich), egg proteins, soy proteins,

etc. How is a consumer to decide? Many factors should be considered

when choosing a protein supplement. These include: organoleptic traits

(e.g. taste, texture, aroma), price, protein content per serving, and

quality. Traits such as taste, texture and aroma are important because

it is almost impossible to regularly consume a product (which is suggested

for best results) if it is a terribly unpleasant experience. Price in

relation to protein content is also significant to consider as a method

to ensure that a "good price" is not an indication of low protein content

or that a premium price isn't simply a fee for a "brand name". Though

all of these factors are worthy of attention, primary consideration

should be paid to protein quality when choosing a supplement.

Evaluating

Protein Quality

There are several ways to evaluate protein quality. It is important

to realize that protein quality is not simply a subjective physical

attribute, rather it is a biochemical/ physiological characteristic

that is evaluated based upon a protein's amino acid pattern, digestibility,

assimilation, and utilization traits. After all, consuming protein is

not beneficial if the body cannot digest, absorb and use it. Biological

Value (BV), Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER) and Protein Digestibility

Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAA's) are some of the more common

indices typically cited in textbooks, advertisements and industry-related

periodicals. While these measures can be useful for comparing one protein

to another, each of them is inherently laden with

procedural variations and potential interpretative errors and should not be used

as the sole basis for promotional claims. As an example, Biological Value (BV),

argualbly the most frequently employed method for evaluating the quality of a

protein, estimates the percentage of absorbed nitrogen (N) that is retained by

an organism. Put another way: BV = (retained N ÷ absorbed N) x 100. If

you stop to think about this calculation for a moment you will probably realize

that it is impossible for the body to retain more nitrogen than it absorbs, yet

this is the scenario that would be required to end up with a BV of > 100. So

how is it that some companies claim BVs in excess of 130? Good question. There

are many possible explanations of how these figures were obtained; experimental

errors/variations including: incorrectly calibrated equipment, methodological

variations, inaccurate calculations and faulty study design are a few. Data falsification,

marketing liberties (104,130,159...whatever it takes) and/or ignorance on the

part of the copywriter are other less comforting explanations for this trend.

In any case, the scientific community does not acknowledge biological values over

100;

neither should you. It is important to keep in mind that while most, if not all,

of the methods used for evaluating protein quality are less than ideal, these

measures do offer a general indication of how "usable" a protein is

by the body. As a rule, most of the egg, whey, soy and casein commonly found in

protein supplements from reputable manufacturers all rate very well in one or

more of these protein scoring methods.

So

What'll Be? Whey? Casein? Egg? Soy? Or all of the Above

Whey

Protein Concentrate (WPC): Once discarded as "waste", the popularity

of whey has increased dramatically in recent times because of advances in processing

technology. Whey begins as a watery byproduct of cheese manufacturing. In its

crude state, whey is about 93% water, 6.5% lactose, 0.9% protein and 0.2% vitamins,

minerals, and fat-soluble nutrients. In this form, whey is not of much benefit

to athletes, but with gentle low-temperature processing and filtration, this liquid

can be stripped of most of its lactose, fat, cholesterol and water to yield concentrated

whey powders containing anywhere from 34 to 89% protein. It is important to note

that there are significant price and nutrtional value differences between the

various WPCS on the market. A WPC containing 34% protein may cost up to 80% less

than better quality whey protein concentrates with protein contents of 77% or

higher. Most protein powders use a blend of different whey protein concentrates,

isolates and hydrolysates, making it possible to hide inferior/cheaper proteins

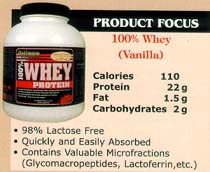

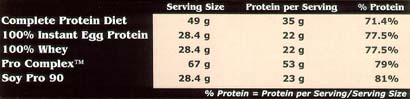

in a product. But there's an easy way to find out... To determine the overall

protein percentage of your supplement, whey

or otherwise, simply divide the protein found in each serving by the

serving size and multiply by 100. Here is an example to help you figure

out how much of your current protein powder is actually protein: 22

g of protein per serving ÷ 28.4 g serving size x 100 = 77.5% protein.

Keep in mind; it is impossible to end up with a product that is 100%

protein. Flavors, colors, sweeteners, micronutrients, etc. that are

used to make these supplements more completely nutritious and enjoyable

to consume, necessarily displace some of the space that could be occupied

by protein. Nevertheless, it's important to account for these fillers,

since grams of protein per bottle is what most consumers are really

after.

Table2

Whey Protein

Isolates (WPIs):

Crude, or sweet dairy whey, can also be "isolated" via cross flow microfiltration

(CFM) or ion exchange (IE) processes to produce whey powders that are

virtually fat, carbohydrate (lactose) and cholesterol free. By definition

WPIs contain >90% protein by dry weight. There are a few premium supplements

that derive all of their protein content from WPIs (one of these is

Iso-Whey by Optimum Nutrition), but WPIs are most often used in conjunction

with Whey Protein Concentrate (WPC) and /or other proteins to boost

the overall protein content of a supplement.

Many people often

ask which isolation process is better. The following paragraphs give

a brief overview of the processes and the potential benefits each has

to offer.

Cross Flow Microfiltration (CFM) is a solvent-free process that uses natural ceramic filters

to separate whey proteins from a variety of undesirables (i.e. fat,

cholesterol, lactose, etc.). Advantages to this process include minimal

protein denaturation, preserved protein microfractions and a better

mineral profile. Whey, like many other proteins, including egg, soy

and casein, is actually a family of different smaller proteins called

microfractions. Glycomacropeptides, alpha-Lactalbumin, Lactoferrin,

Lactoperoxidase, and Immunoglobulins are some examples that you may

have read about in magazines or seen on labels. Because there is some

indication that these protein fractions may play a role in appetite

regulation, immune functioning, neutralizing free radicals and more,

many people prefer CFM since it is better at preserving some of these

fractions than Ion-Exchange. CFM is also generally higher in calcium

and lower in sodium than IE as a result of differences in processing

methods.

Ion-Exchange

(IE) is a process that separates proteins on the basis of their

electrical charge. Unlike CFM, ion-exchange requires the use of various

solvents to create an attractive charge on the proteins. Once charged,

these proteins migrate toward oppositely charged resin beads in the

reaction vessel. The protein can be later removed from the resin beads

by reversing the charge to result in a highly purified WPI. Ion-exchange

WPIs are not typically considered as "native" (maintaining the same

microfraction ratios found in milk) as CFM isolates, but they are richer

in total protein - containing upwards of 97% by dry weight - and are,

therefore, a popular choice among bodybuilders and athletes.

Hydrolyzed Whey

Peptides (HWP): debatably the best - at least in terms of bioavailability

- whey proteins that money can buy. HWPs are short chains of amino acids

(e.g. di-, tri-, poly-peptides) produced by strategically digesting

(with enzymes) various bonds in whole whey proteins. Preliminary research

suggests that HWPs are more easily absorbed (and probably utilized)

than any other protein that we know of. Unfortunately, HWPs have an

extremely bitter taste, so they can only be used in conjunction with

other proteins and added in relatively small amounts.

Casein: commonly

referred to as the "other" milk protein, casein actually comprises over

80% of the total protein in milk. Though not currently "en vogue"

with athletes (due, in large part, to the success of whey proteins),

casein is easily assimilated by the body and rich in all of the EAAs

(see EAA Density graph). Casein is the protein of choice in the pharmaceutical

and food industries where it is used in baby formulas, enteral nutrition

products, cheeses and numerous other applications. Many meal replacement

products also take advantage of casein's thickening properties to improve

overall taste and mouth-feel. As an added benefit, casein is digested

more slowly than whey, egg or soy to provide a constant stream of amino

acids to hungry muscle tissue. In other words, casein may offer anti-catabolic

properties. So, contrary to what you may have heard, casein is an expensive

(even more so than most whey proteins), high-quality protein and deserves

to occupy a place in every athlete's diet.

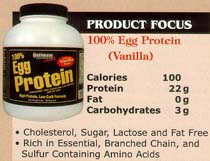

Egg Albumen:

also known as egg white, is a complete protein and an excellent source

of sulfur containing amino acids. Once the staple of bodybuilders everywhere,

egg protein has recently taken a "back seat" to whey. Although we're

not going to suggest that egg albumen is superior to whey, nutritionists

generally refer to egg as the "gold standard", or protein to which all

others should be compared. Obviously, some would argue that this opinion

is dated, in light of what we know about whey, but there's no denying

that egg proteins do offer certain advantages. For starters, egg white

proteins are lactose-, fat-, and cholesterol-free. Egg proteins also

contain high levels of sulfur, essential, and branched chain amino acids.

Finally, egg albumen contains niacin, riboflavin, magnesium, potassium,

chloride and other nutrients that athletes need, so don't forget about

this great product the next time you're in the market for a protein

supplement.

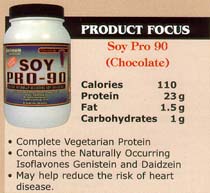

Soy Protein: is

unique in that it is a complete, meaning it contains all of the EAAs

in adequate amounts, vegetarian protein. Though soy has been a staple

of the Asian diet for thousands of years, this vegetable-based protein

has just started to gain recognition in the U.S. Much of this newfound

popularity can be attributed to three factors: (1) Recent advances in

soybean processing techniques. (2) The identification and isolation

of health promoting compounds called isoflavones. (3) The recent approval

of a "heart-healthy" claim by the FDA.

Thanks to new processing

techniques, the quality of the soy protein-based supplements that are

currently available are much higher than those previously marketed.

These techniques enable manufacturers to selectively remove non-protein

components (fibers, oils, minerals, etc.) and better isolate two key

components in soy: protein and isoflavones. Soy Isoflavones are naturally

occurring compounds that appear to act as antioxidants and natural hormone

modulators in the body. At least two, genistein and daidzein, isoflavones

are believed to be biologically active in a variety of capacities in

the human body. Though the reasons "why" are not yet well

understood, research comparing Asian Versus Western diets suggests that

something in soy may play a significant inhibitory role in certain cancers,

osteoporosis and atherosclerosis development. The body of research done

on soy and cardiovascular health is so strong that the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) has recently approved a Health Claim stating that

diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol that include 25 grams of

soy protein a day may reduce the risk of heart disease. Keep in mind;

this is monumental seeing as how there are less than ten allowable Health

Claims for all foods! If you still need more reasons to convince you

to try soy, consider the following: Products containing soy protein

isolates typically yield more protein per serving than whey, egg or

casein (please refer to TABLE 2). Soy is naturally free of cholesterol.

Soy is non-animal based and is, unless mixed with other animal products,

suitable for vegetarians.

Putting

it all Together

If we accomplished our objectives, you are beginning to question much

of what you have seen and read about proteins up until now. Although

much of the bio-speak that spews from the bodybuilding media is questionable,

you can pretty well bank on these eight points: (1) proteins have different

amino acid patterns/ratios; (2) some proteins are more digestible than

others; (3) proteins are absorbed at different rates; (4) blends containing

multiple proteins may be more advantageous than proteins derived from

a single source; (5) whey, egg, casein and soy are all very high quality

proteins with different taste and functional characteristics; (6) athletes

require more protein than sedentary individuals; (7) a

high quality protein will be easily digested absorbed and utilized by

the body; (8) every year will bring new hype and new supplement companies

out of the woodwork. Do yourself, and your pocketbook, a favor...QUESTION

WHAT YOU READ AND HEAR AND LEARN AS MUCH ABOUT PROTEIN SUPPLEMENTS AS

YOU CAN.

Information provided by Optimum

Nutrition